The recent CMS Undesirable Business Practice Declaration

28 May 2021

11.4 min read

Apricots and Celestials

Medical schemes and providers

Simplistically, this is precisely how medical schemes and provider networks function. Medical schemes negotiate with the various hospital groups, who then compete for increased volumes by presenting discounted tariffs and other value adds. Medical schemes select the hospital group(s), representing the strongest value proposition to the Scheme and its members, and then channel patients towards these hospital group(s). Co-payments apply when members voluntarily make use of non-network hospitals. By law, medical schemes are prevented from applying co-payments to the involuntary use of non-network hospitals, such as in the event of emergencies. Network arrangements have empowered schemes to reduce their contributions by up to 15% (without any reductions in available benefits). This increases access to care and allows more people to belong to medical schemes. This is not to say that medical schemes cannot improve how they select network participants and manage networks.- Some Schemes lack the technical capacity required to analyse or benchmark the costs associated with different hospital groups in a robust way. The hospital groups with the highest discounts and the lowest tariffs are not necessarily the most affordable. Affordability is a function of prices, utilisation and quality. For example, a hospital group with lower tariffs but average stay may represent a poor value proposition. Actuarial tools such as the Insight Diagnosis Related Grouper (DRG) are needed to analyse and benchmark costs properly.

- Some medical schemes have not given sufficient attention to matters other than the cost of care when selecting network participants. Patient experience, healthcare outcomes (the quality of care) and economic empowerment and transformation are important factors to consider when appointing a network.

- Some medical schemes do not adequately engage with hospital groups and are not sufficiently transparent when selecting network participants. This means that not all hospital groups are given a fair opportunity to participate on networks.

Why would the Declaration make hospitalisation more costly for medical scheme members?

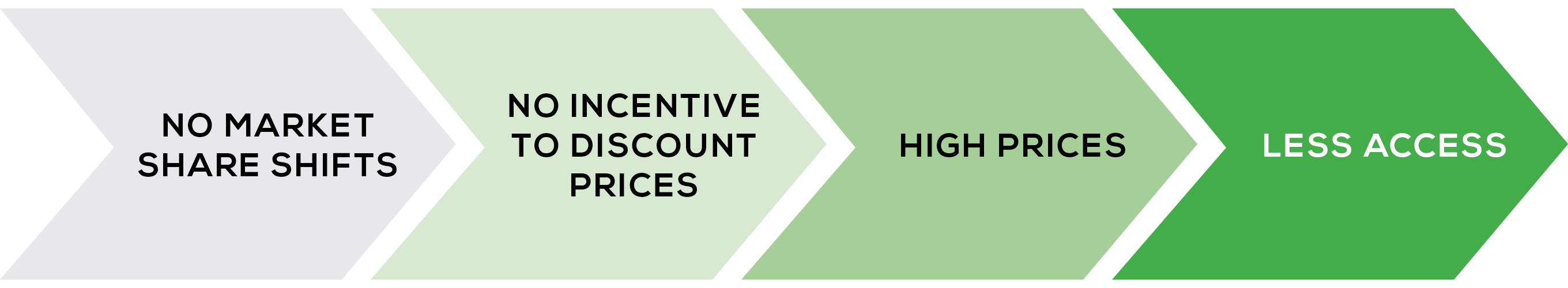

Consider the cell phone example above. You secured favourable discounts because the manufacturer knew that the cost of exclusion exceeds the cost of discounts. Specifically, Celestial provided a R2,000 discount to secure its status as a preferred manufacturer. On the other hand, Apricot is now the non-preferred manufacturer and would have had to resign itself to reduced sales as employees opt for Celestial to avoid co-payments. If Apricot wanted to prevent this, it would have to write off the R3,000 co-payment (which is analogous to giving a R3,000 discount). Such a large discount would not be economically viable to Apricot. Now assume that regulations had prevented companies from applying a co-payment, which is more than the discount offered by the preferred manufacturer (which is what the CMS announced in Circular 24 and its attendant Government Gazette). The advantages of being a preferred manufacturer would quickly dissipate, as would the disadvantage of not being a preferred manufacturer. Discounts would soon become a thing of the past. The non-preferred manufacturer could maintain its market share by announcing that it would write off co-payments (which, in our example, effectively means Apricot would have to discount prices by only R2,000 and not R3,000 because of the imposed limitation). Given that co-payments could no longer exceed the discounts provided by the preferred manufacturer, this is now economically viable. The preferred manufacturer would not experience an increase in market share. The preferred manufacturer would be no better off than the non-preferred manufacturer, and there would be no incentive to continue to offer discounts. If the preferred provider does not experience the intended increase in market share, the net result would be as follows: We can contemplate a medical scheme attempting to negotiate discounts once the Undesirable Business Practice Declaration comes into effect:

We can contemplate a medical scheme attempting to negotiate discounts once the Undesirable Business Practice Declaration comes into effect:

Scheme: “If you give us a 20% discount on your tariffs, I can encourage more members to make use of your services and channel volumes to you.” Hospital: “No, you can’t.” Scheme: “Of course I can; I will impose co-payments on your competitors to encourage members to make use of your hospital. It is a win-win situation: you will get more volumes, and the members of our scheme will get lower tariffs, which will translate into lower contributions.” Hospital: “The Undesirable Business Practice Declaration limits the co-payment you can impose on my competitors to the 20% discount you are asking for. My competitors will simply waive the co-payment, and I will be stuck with the same volume of business but at a lower price. I would be foolish to agree to such an arrangement. I bet my competitors will come to the same conclusion if you were to offer the same terms to them. I would rather keep my undiscounted tariffs and my current market share, thank you very much.”

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

The Declaration gives rise to what game theorists and negotiation experts refer to as a “Prisoner’s Dilemma”. Providers will realise that they would be foolish to offer discounts in anticipation of higher volumes, as the eventual outcome of such discounts would leave them worse off, both individually and collectively. Rational providers will realise that it is in their best interest to cease offering discounts in return for volumes. Contributions would become increasingly costly, and access would be reduced. Members with limited financial means would be worst affected since they would have to forgo medical scheme cover if they can no longer afford it.Procurement should not only consider the cost. What about quality?

There are many other compelling and non-financial reasons why medical schemes want to levy co-payments that exceed the discounts offered by network providers. Irrespective of the willingness of non-network providers to match the discounts offered by network providers, the Scheme may wish to channel its members to network providers.- Network providers may be associated with superior healthcare outcome.

- Network providers may be associated with a superior patient experience.

- Some network providers may have outstanding empowerment credentials.

- Network providers may be more cost-effective despite higher tariffs noting that cost is a function of both utilisation and tariff.

1 There is a broad range of additional factors which medical schemes should consider when selecting network participants. This includes but is not limited to the quality of care, accessibility, and the development of an increasingly competitive healthcare environment.

For more information and/or to schedule a discussion, contact: Masimba Mareverwa masimbam@insight.co.za 0836416525

Get an email whenever we publish a new thought piece

In 2023, Insight Life Solutions conducted a series of surveys to seek South African life insurers’ views on specific IFRS 17 topics. The surveys aimed to summarise the progress made

3.2 min read

Insight Life Solutions conducted a series of five surveys in Q3 2022 to seek South African life insurers’ views on specific IFRS 17 topics. The surveys aimed to summarise the

3.5 min read